History of the Korean Ji Pang E (Cane)

It was almost sunset as Jong Shim made his way down the

narrow street toward his home. Suddenly three men appeared

in front of him and demanded his money. The bandits could

see this was a man of wealth and their efforts were going to

be well rewarded. So when Jong refused to give them his

valuables they rushed in to teach time a lesson. However, it

was the bandits who were about to receive their first lesson

in the use of the deadly Korean Ji Pang E (cane).

The first bandit's head snapped backward from a blow that

was delivered so fast he never saw it coming. The second

bandit charged forward attempting to crush Jong's head with a

staff. But the staff never found its target, and the bandit

felt a hard jolt and a piercing pain in his back as the ji

pang e struck a hyel do (vital point). The man dropped to

his knees helpless, unable to move his legs. The third

bandit drew his knife and thrust it toward Jong's stomach.

The bandit saw the knife go sailing through the air just a

split second before he found himself airborne. A moment

later he found himself in a crumpled heap on the ground next

to his friends.

The first bandit's head snapped backward from a blow that

was delivered so fast he never saw it coming. The second

bandit charged forward attempting to crush Jong's head with a

staff. But the staff never found its target, and the bandit

felt a hard jolt and a piercing pain in his back as the ji

pang e struck a hyel do (vital point). The man dropped to

his knees helpless, unable to move his legs. The third

bandit drew his knife and thrust it toward Jong's stomach.

The bandit saw the knife go sailing through the air just a

split second before he found himself airborne. A moment

later he found himself in a crumpled heap on the ground next

to his friends.

The confrontation was over in just a few seconds, and Jong

was unhurt as he stood looking at the bandits sprawled on the

ground. They were unconsciousness and completely at Jong's

mercy.

As the first man regained consciousness, he saw Jong bent

over one of the other bandits. Jong was applying healing

pressure to the man's back, and soon the man was able to move

his legs again. Jong methodically went from one bandit to

another until each was able to stand on their own. The

bandits, puzzled but grateful by this act of kindness,

quickly left, more knowledgeable men. They had learned what

an effective weapon the Korean cane could be in the hands of

an expert like Jong Shim. Only much later did they discover

Jong was an instructor of martial arts for the guards of the

royal family of the Korean Kingdom of Silla.

In Today's society it is against the law to carry almost

any type of object which may be deemed as a weapon. The cane

may very well be one of the last "permissible" weapons

available which you can carry to defend yourself without

violating the law. Fortunately, the cane is easy to learn,

versatile and an extremely effective weapon for self-defense.

The use of the cane in not uncommon to other mu do (martial

arts). Many of the Korean martial arts include some

instruction in the use of the ji pang e for self-defense. To

see how the cane was used as a defensive weapon in ancient

times, let's take a look at its evolution in Korea.

Korean monks sometimes carried the cane during their travels.

The cane served them in several different ways; it was used

to help them maintain their balance climbing hills and over

rough terrain, and it was also used to help the monks defend

themselves from bandits and wild animals during their travels

throughout the country. Some Buddhist temples had animals

they raised, and the monks would used their canes to help

oversee their herds and flocks. If the temple was attacked,

the cane could quickly become a defensive weapon, used to

drive the invaders off.

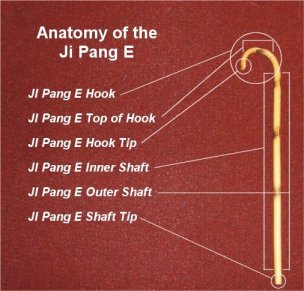

Types Of Canes

There are primarily three different types of canes. The

first type was from five and one-half to seven feet in length

and curved like a hook at one end, similar to the canes

carried by shepherds. The second type of cane was about

waist-high, straight, with either a knob or short straight

handle. The third type of cane is the type most commonly

used both in the past and today. It is about waist-high,

straight and has a curved (hook-type) end used as the handle.

The common people favored it for its practicality.

The Shepherd's Cane

There are primarily three different types of canes. The

first type was from five and one-half to seven feet in length

and curved like a hook at one end, similar to the canes

carried by shepherds. The curved portion of the cane was

quite often used for the application of kwan jyel sul (joint

manipulation techniques). This was the type of cane the

monks used for herding

animals and sometimes as a walking pole on their travels.

Sometimes, in order to escape from bandits, a monk would use

the curved portion of this long version of the cane, to hook

a high branch of a tree, climb up the cane to the branch,

then pull the cane up with him. This another example of how

certain monks got the reputation of being able to become

invisible. The monk could remain hidden in the tree until

the bandits had moved on. If it became necessary, he could

use the cane to strike the bandits as they passed under the

tree, or he could use the hook portion of the cane to pull

them off of their horses. When the encounter was over the

monk would again hook the cane to the branch, climb down,

then continue on his way.

Another favorite tactic the monks used was to hook the top of

a high wall with the ji pang e, then pull themselves to the

top of the wall and over. A perfect example of how they

could "walk through walls".

The Aristocrat's Cane

The second type of cane was about waist-high, straight, with

either a knob or short straight handle. This type of cane

was not as popular with the monks because it was not as

practical for their needs. However, the straight cane was

used very often by the hwa rang, members of the upper

classes, and members of the royal families.

The second type of cane was about waist-high, straight, with

either a knob or short straight handle. This type of cane

was not as popular with the monks because it was not as

practical for their needs. However, the straight cane was

used very often by the hwa rang, members of the upper

classes, and members of the royal families.

The cane became not only a sign of importance and wealth, but

a deadly weapon for self-defense. Many times the handle bore

the crest of the family, and was made of gold or silver with

jewels embedded in it. In some cases a blade was concealed

in the cane. A sharp pull on the handle and the blade would

be ready for action. For the upper classes the straight cane

was what suited their needs for both appearance and self-

protection.

During the sixth century, Korea was divided into three

separate Kingdoms; Koguryo, the largest of the three, was in

the north, Baek-Je, the second largest was located in the

southwest portion of the Korean peninsula; and Silla, the

smallest of the three Kingdoms, was in the southeast. It was

in the Kingdom of Silla where a group of young warriors

called the Hwa Rang (flowering youths) were created. The hwa

rang were instructed in several different forms of defense

were also part of Buldo mu do (Buddhist

martial arts); kwan jyel sul (joint manipulation), hyel do

sul (striking vital points of the body), and ji pang e sul

(cane techniques). They were instructed in the use of the

cane by Korean monks including the famous Won Kang. As part

of their specialized training, the hwa rang trained in the

application of techniques using the cane for striking,

throwing, controlling, and the application of kwan jyel

defenses. They also carried the cane as a sign of their

social position and status.

The Everyday Cane

The third type of cane is the type most commonly used both in

the past and today. It is about waist-high, straight and has

a curved (hook-type) end used as the handle. The common

people favored it for its practicality. Korean Buddhist

monks also used this type of cane for self-defense because

the hooked portion aided them in the application of kwan jyel

techniques, allowing for better control of an opponent

without the use of excessive force.

Today the cane may be used as a means to defend yourself.

You need not use an excessive amount of force to subdue an

opponent, you can use kwan jyel techniques to immobilize the

opponent by using the cane to help augment the techniques.

The elderly can use kwan jyel techniques with a cane for

self-defense with very little training.

The cane, combined with kwan jyel techniques, is one of the

most practical and useful tools for self-defense you may find

today. Be sure to use extreme caution when working with cane

techniques. You will be able to exert much more power than

you believe you can when you use the leverage of the cane to

give added strength to your techniques. Always let your

instructor guide you each step of the way with your training.

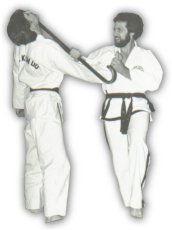

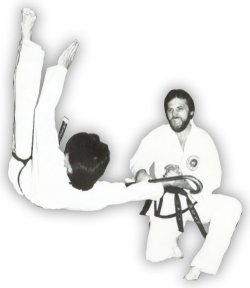

The following techniques are from Grand Master Benko's book: "Korean Cane Techniques (Ji Pang E Sul)" .

The technqiues are performed by Master James A. Benko, Master Gregory Westphal, and Master Philip Curell.